To stick to the world’s climate goals, the construction of new fossil fuel infrastructure without a way to remove their carbon emissions must grind to a halt globally, including in Louisiana where several facilities are planned.

That was one of the top messages of the latest international climate change report on mitigation released on April 4.

Earlier this year, Louisiana became the first Deep South state with a plan for cutting its carbon footprint. However, while Gov. John Bel Edwards advocates for a cleaner future, it remains unclear how and when the state will tackle the influx of an additional 101 million metric tons of emissions from future industrial projects that have already been approved.

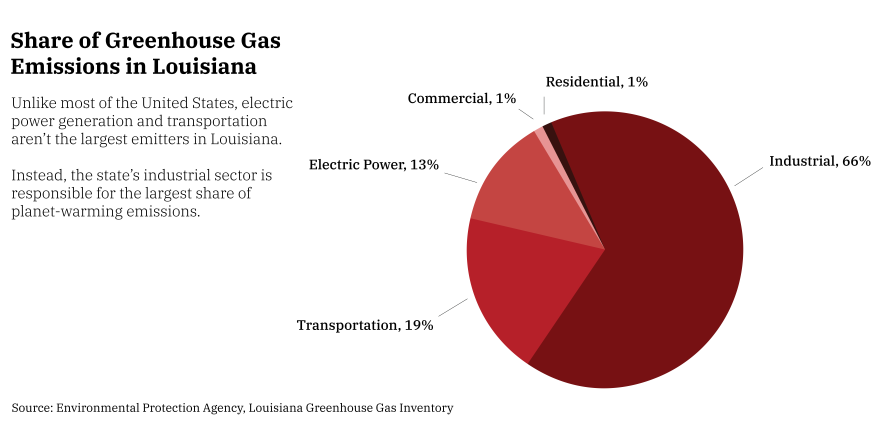

To put that number into perspective: Louisiana is already responsible for a relatively high amount of carbon emissions compared to its population size. It’s fifth in the nation for emissions per capita. The state emitted 216 million metric tons in 2018, according to Louisiana State University’s 2021 greenhouse gas inventory.

Two-thirds of that already comes from the industrial sector, which is widely considered to be the most challenging to decarbonize. If all of the permitted projects moved forward, it could potentially bring the total industrial emissions to 242 million metric tons.

In the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report, the authors said the tools needed for Louisiana’s industry to mitigate emissions are already available and ready for use, yet the vast majority of those proposed projects don’t have plans in place to eliminate, or even lessen, their impact.

“‘It is a global problem, and it's got to happen,” said Jae Edmonds, a lead author on the IPCC’s April report. “You can't let off the hook any major economy in the world, and you can't let off the hook any sector. They all have to be headed to zero.”

Edmonds said the longer companies and governments wait, the longer it will take the world to reach zero emissions and limit global warming. Past climate reports warn that more warming could have dire impacts for coastal Louisiana.

The financial risks

But pivoting to those plans is easier said than done, according to industry officials, who said the economic risk is keeping more companies from investing in the technologies needed to significantly cut emissions.

In the industrial sector, Edmonds and other researchers said steep emission reductions will require a combination of things: increasing energy efficiency, electrifying operations, switching from fossil fuels to another heat source and offsetting any remaining emissions.

Industry advocates have zeroed in on the ability to offset emissions. That can be done with nature by restoring habitat, like trees, that sequesters carbon, or with existing technology known as carbon capture and storage that has been pushed by the industry as a critical tool for cutting its impact through the technology.

But even that hasn’t been widely implemented on a commercial scale, and companies are slow to roll out their own plans to build carbon scrubbers.

Nathan McBride, the regulatory manager for the Louisiana Mid-Continent Oil and Gas Association, said that’s because constructing the infrastructure to start capturing carbon is expensive, and there simply isn’t an economic incentive for companies to store it.

“Making that investment viable, there has to be some kind of a return. It doesn’t have to be a large return, but there has to be some kind of a return in order for companies to stay in business,” McBride said.

To McBride, that means increasing the value of the federal tax credit available to companies, known as the 45Q tax credit, for each metric ton. He’d also like to see more governments help in building the infrastructure, such as pipelines to carry the CO2, which costs hundreds of millions of dollars and makes startup costs high.

Not all investments are as risky, though. Making industrial plants more efficient would reduce consumption and save on energy costs in the long-term, offering an economic incentive. Yet McBride said that kind of progress in Louisiana has still been slow.

“Energy efficiency is something I know one a lot of our facilities are emphasizing,” he said. “It just takes time. … You make too many changes up front, it can negatively impact cost (to customers.)”

Current proposals in Louisiana

New facilities aren’t required to submit plans for increasing energy efficiency or mitigating emissions during the permit process, so most don’t have one.

But LSU professor David Dismukes expects future projects to face increasing pressure to mitigate any emissions. He’s the executive director of the university’s Center for Energy Studies and also authored the state’s greenhouse gas inventory.

That has already begun with last year’s high-profile announcement of a new $4.5 billion blue hydrogen facility in Ascension Parish, expected to come online in 2026.

Air Products’ plant would produce hydrogen using natural gas as a feedstock and rely on carbon capture and storage to capture 90% of its emissions. Other plants could then use that lower-carbon hydrogen to start decreasing their own use of straight fossil fuels.

“There's been a ground swelling of interest in these areas coming from industry people and others that just simply did not exist a couple of years ago,” Dismukes said.

But Air Products is possibly the only facility planning to meet the IPCC report’s threshold for meaningfully abating emissions, which said projects should offset or capture 90% or more. Most project proposals in Louisiana don’t meet the same standard.

For example, Venture Global, a liquefied natural gas exporter, announced plans last May to capture a total of 1 million tons of carbon per year from its three terminals planned in south Louisiana.

But, altogether, those terminals — nicknamed “carbon bombs” by climate advocates — are expected to release up to 20.5 million tons of greenhouse gas annually. This means it might capture just 5% of total emissions.

“We're going to have to step our game up a little bit on that,” Dismukes said.

‘The wrong direction’

Environmental and renewable energy advocates like Logan Burke aren’t as confident that companies will adjust their own plans to include carbon-cutting measures. While some in Louisiana's legislature want to prevent state agencies from regulating greenhouse gas emissions, she said that’s “the wrong direction.”

Instead, Burke, who is the director of the Alliance for Affordable Energy, argued Louisiana should stop welcoming new industrial projects and make evaluating greenhouse gas impacts part of the permitting process.

“If a new facility is slated to come to Louisiana, the very first question that the Louisiana government must ask is ‘can this be a zero greenhouse gas emission facility?’ And then the onus is on that industrial facility to make it so,” she said.

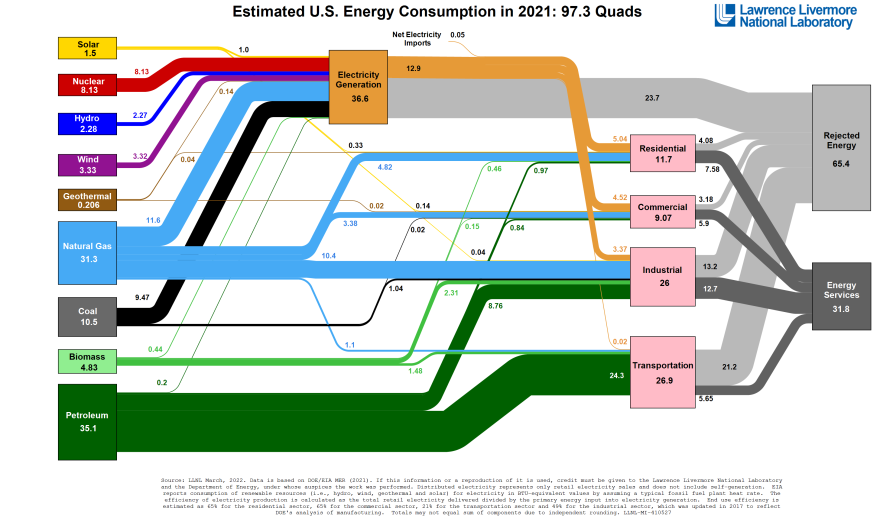

Burke pointed out that much of the energy already produced from fossil fuels in most sectors isn’t used. In 2021, the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory estimated that just over half the energy produced in the industrial sector goes to waste.

“That means we're wasting fossil fuels in a way that suggests we certainly shouldn't be going to get more of them out of the ground,” she said.

Historically, Sierra Club organizer Darryl Malek-Wiley said Louisiana regulators have focused on whether a permit meets federal standards, rather than considering the “moral imperative” of reducing carbon emissions.

“We have this policy that we want to go to net zero by 2050,” he said. “Where are the legal teeth to force companies to make investments moving toward that? That’s what we’re lacking.”

Right now, while information on projected greenhouse gas emissions is collected, it has no bearing on whether a permit is issued, he said.

Louisiana’s Climate Action Plan calls for the Department of Environmental Quality and Department of Natural Resources to craft a Net-Zero Industry Standard and industry efficiency standards to set rules for facilities. Industry groups also opposed both measures, arguing the transition should be determined by market forces, not regulations.

The Governor’s Office is still evaluating the extent that existing authorities can be used to implement the plan, said Harry Vorhoff, deputy director at Louisiana Governor's Office of Coastal Activities.

If creating such standards does not fall within the executive power, it might require approval from Louisiana’s largely industry-friendly legislature.