On the ballot for parts of East Baton Rouge Parish, there’s a measure to create a new city: The City of St. George. It’s the first step to carving out a new school district, separate from East Baton Rouge Parish Schools.

Supporters say St. George will allow more local control over taxes and improve education.

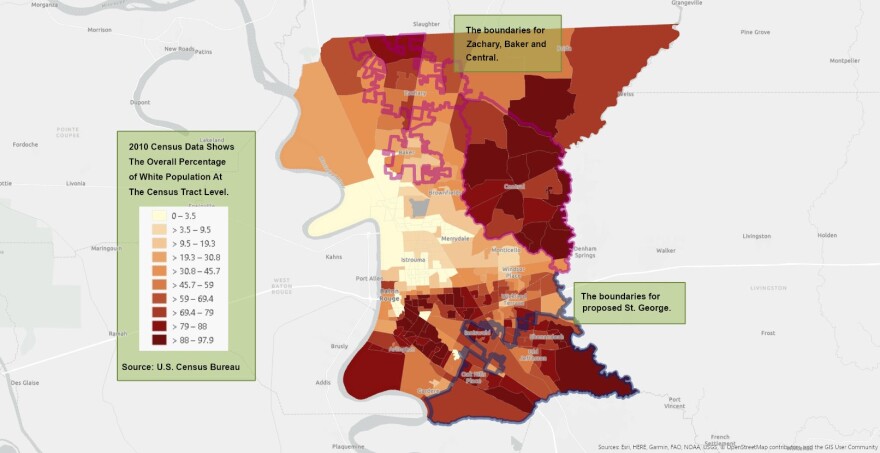

But the proposed boundaries of St. George encompass one of the whitest, most affluent sections of a diverse parish. Opponents say if the St. George organizers succeed in creating a new city and school district, they will drain the East Baton Rouge Parish school system of its remaining white students, and one of its most important tax bases. That would leave the City of Baton Rouge and its students with even fewer resources.

Researchers say St. George effort is part of a national trend of “splinter school districts” worsening segregation and racial disparities across the South. In Baton Rouge, the proposal has brought to the fore the parish’s troubled legacy of school segregation.

‘That Treasure Chest of St. George is Going Away’

Supporters of St. George say the creation of the proposed city is not just about taxes, or crime or even schools - it’s about America.

“This is about a real part of American history that we have forgotten,” La. State Representative Rick Edmonds (R-Baton Rouge) told a crowd gathered in the giant, airy sanctuary at Woodlawn Baptist Church. It was an evening in early September, and several hundred people were seated in the pews to rally and gear up for the impending election.

“Self-government is the most important principle in the United States Constitution. It's just who we are,” Edmonds told the crowd.

"They take our money, and spend it elsewhere, which is the true reason they are opposed to us" - Andrew Murrell

Later, St. George organizer and attorney Andrew Murrell made a more nuts-and-bolts case for the proposed city.

“We've been paying $48 million in taxes and only getting $34 million in services,” he told the crowd, citing numbers from a report commissioned by St. George organizers.

“They take our money, and spend it elsewhere, which is the true reason they are opposed to us. They are opposed to us because that free money, that treasure chest of St. George, is going away,” he said.

The vote on Oct. 12 is about whether to form a city. But St. George organizers say the ultimate goal is to carve out a new St. George school district, separate from East Baton Rouge Parish Public Schools. Demographic data show a new St. George school district would worsen racial segregation in the parish’s public schools. While East Baton Rouge Parish is 45 percent black, the proposed city of St. George would be just 12 percent black. St. George would also be significantly wealthier.

Those demographics were on display at Woodlawn Baptist. Nearly everyone in the pews was white. And most here said they pay for private school.

“I would never put my child in East Baton Rouge Parish Schools,” one mother said, who declined to be identified.

A Call For 'Local' Schools

St. George organizers have been accused of racism by opponents of the effort

“There are some racial implications,” La. State Senator Karen Carter Peterson (D-New Orleans) began in an impassioned speech on the Senate floor in May over a bill to help the proposed city collect taxes during a transition period.

“Why should a select few be able to pull out, after all the tax dollars have been contributed to your area to the detriment of a poor black neighborhood in this parish? I’ll be damned! It’s wrong!” she said.

"Some of this also I think reflects, quite frankly, a willful ignorance of the history of race" - Albert Samuels

But St. George supporters don’t see it that way. Baton Rouge mom Stacy Hudson, who is white and in her thirties, has been volunteering for the St. George effort for years. Hudson said she’s always been politically active. In fact, she met her husband Dwight Hudson at a Tea Party rally at the state capitol about 10 years ago. Now her husband represents their area in the Baton Rouge Metro Council.

“Our whole relationship has been trying to do better for our area and for our kids’ future,” she said.

Hudson and her husband have two children. The oldest is in pre-K at their neighborhood public elementary school. But she’s worried about the quality of the public school options that will be available to her in middle and high school. Many of the area’s schools have a C-rating from the state, based on standardized test scores.

“I am a product of the [East Baton Rouge] Parish Schools and the problems that existed when I was in school are still there,” Hudson said, citing concerns over teacher pay and working conditions.

Hudson said a St. George school district would try to pay teachers more and solve some of the problems that East Baton Rouge has struggled with. And she believes allowing students to go to school closer to home will help.

“It will be more local,” Hudson said. “When I grew up, I remember when things changed, and my friends that were across the street from me were sent to different schools. And it really just changed the environment of the neighborhood.”

Hudson is referring to a period during the 1980s and 1990s, when East Baton Rouge Parish Schools began busing plans in an attempt to comply with a federal desegregation order.

Hudson said St. George is about taking control of local schools and improving them -- not race.

“We've been called racists just because we support it,” Hudson said. “But I'm just going to be frank: my black neighbors will still be my black neighbors, and they'll still walk to school with my daughter.”

Hudson may have some black neighbors, but there’s no question the City of St. George would be a lot whiter than the rest of the parish. Still, Hudson said it’s not their goal to exclude anyone.

“I don't think it's an issue. People want to make it an issue because they don't have any other issues to stand on,” she said.

“They’ve Just Been Chipping Away”

A couple weeks after the rally at Woodlawn Baptist, another group of people are meeting inside another, very different East Baton Rouge church. Second Mount Olive Baptist has an African-American congregation, and is located just inside proposed St. George. The sanctuary is cozy, with just five rows of wooden pews and a worn red carpet. Organizers opposed to St. George have gathered people here, including East Baton Rouge resident Arthur Pania, who is black.

“You have to get back to why this started, and what’s the core problem, and why it truly started,” Pania said.

"I remember when things changed, and my friends that were across the street from me were sent to different schools. And it really just changed the environment of the neighborhood." - Stacy Hudson

Pania, like many here, believes the St. George effort is part decades-long resistance by white residents to federal school desegregation laws.

He points to other school districts, Zachary and Central, that have been carved out of East Baton Rouge Parish over the years since the federal courts mandated integration through bussing. While East Baton Rouge Parish Schools are just 12 percent white, Zachary, carved out of East Baton Rouge in 2002, is 42 percent white, and Central, carved out in 2007, is 73 percent white.

“They’ve just been chipping away,” Pania said. “And now this is their last and final attempt to actually get the last piece of the puzzle, to actually fully break away to have a majority white school system.”

‘Splinter’ School Districts

The St. George effort is part of a national trend some call “splinter” school districts - a white section of a large, diverse parish or county-wide school system splits off. And studies show this trend is worsening school segregation, especially in the South.

“This is the latest effort in this decades-long campaign to undermine Brown V. Board of Education. And it’s probably the one, that if it succeeds, would be the most devastating,” Southern University of Baton Rouge professor Albert Samuels said. Samuels studies school desegregation in East Baton Rouge Parish.

When Samuels talks about Brown V. Board of Education, he’s referring to the 1954 Supreme Court decision that declared racially-segregated schools unconstitutional. Getting school districts to comply with the ruling wasn’t easy. In fact, East Baton Rouge Parish had one of the longest-running desegregation cases in the country -- lasting nearly half a century. As the courts enforced integration in East Baton Rouge Parish, many white families resisted through white flight: they left the parish, or paid for private school, or -- in the case of Central and Zachary -- carved out their own school districts.

“The net effect of course of all of this is that it's very difficult to desegregate a system when most of the whites pull out of the system,” Samuels said.

"Middle class families in this parish shouldn't be forced to fund a private education" - Andrew Murrell

Samuels said the breakaway of St. George would drain the East Baton Rouge Parish schools of many of its remaining white students. There are fewer than 5,000 white students in East Baton Rouge Parish schools, and about 2,000 of them live in the proposed St. George area.

Samuels said when white students leave a school district they take the opportunities that follow them. School funding comes in part from property taxes, which means affluent areas can raise more money. State estimates show a school district that matches the boundaries of St. George would have $4,000 more per student than East Baton Rouge Parish Schools. So while white parents who support St. George want better public schools for their children, Samuels said the end result would be a worsening of racial disparities.

“Some of this also I think reflects, quite frankly, a willful ignorance of the history of race, and of the history of race particularly in East Baton Rouge Parish,” Samuels said. “It reflects a basic denial that the situation that exists now is related to decisions that were made before time.”

Racism is more than a matter of individual prejudice, Samuels said.

“If it’s just individual prejudice, and I can say ‘Well, I'm not prejudiced!’ -- that makes it easy….However, we have a hard time acknowledging how systems work -- that racism is also a system.”

The Map

One major point of contention in the St. George debate is how organizers drew the proposed boundaries.

On a sunny evening in mid-September, Baton Rouge mom M.E. Cormier took me on a tour of proposed St. George. We rode through the upscale suburbs in her black minivan. In the back were two empty car seats, and in the trunk a stack of yard signs rattled around. They read “No St. George.”

Cormier, who is white and in her thirties, is the lead organizer of the opposition to St. George. She lives just outside the proposed boundary, in incorporated Baton Rouge. She’s frustrated with claims by St. George organizers that they are subsidizing the rest of the parish with their tax dollars.

“They want to take their money and only spend it in their area, and they don't want their resources to go to anybody else. But that's not how communities work. That's not how civilization works,” Cormier said.

Cormier has lived in this corner of the parish all her life. Her oldest child attends the same public elementary school she did back in the 1980s. In 1997, more than 40 years after Brown V. Board of Education, Cormier was one of thousands of students in East Baton Rouge Parish who switched schools to comply with a federal desegregation order.

"It's quite clear the distinction between what is and is not included in the St. George map" - M.E. Cormier

Cormier has watched over the last couple decades as more and more white families moved to this corner of the parish, and grassy fields gave way to upscale suburbs and shopping centers. Driving through, we pass rows of large, modern homes with perfectly manicured lawns.

“Beautiful homes,” Cormier said. “All previously undeveloped farmland or grassland before.”

Then, we turn off the main road into a neighborhood where the homes are older and more modest -- single-story ranches mostly. Finally we arrive at an apartment complex. The fences are grayed and wonky, the gutters have broken away from the roofs, and one unit has been completely torn down.

While the majority of this southeastern corner of the parish is white and affluent, this small neighborhood is majority middle or low income, and black, and it’s been sliced right out of the middle of the proposed map of St. George, as if with an Exact-O knife.

Cormier pulls up the map on her phone to show me the hole this neighborhood forms in the center of St. George. There are also several other neighborhoods that border the proposed city -- and in fact were included in an earlier St. George effort. Many of them are apartment complexes. And while most of the St. George area is white and affluent, many of these excluded areas are majority black or latino.

“It’s quite clear the distinction between what is and is not included in the St. George map,” Cormier said.

Because of Louisiana’s laws about city incorporation, the people who live in these excluded areas won’t get to vote on whether the would-be city surrounding them becomes a reality.

St. George Is About America

The map of proposed St. George makes it hard to ignore race as a factor. But proponents, like Andrew Murrell, the St. George organizers’ designated spokesman, are adamant that racial segregation is not their goal.

"This is about a real part of American history that we have forgotten" - Rick Edmonds

Murrell, who is white, runs a law practice out of a converted ranch-style home in Baton Rouge. He said he got involved in St. George because he wants to improve the area’s public schools. Murrell grew up in Texas, where he went to public school.

“When I got to [East Baton Rouge] parish, I couldn’t comprehend the fact that there are all these private schools around,” Murrell said.

But like many middle class and wealthy families in this part of East Baton Rouge Parish, Murrell now pays thousands of dollars a year to send his children to private school.

“From my law practice, I've had clients whose kids were beaten up and abused in the school system by other students while teachers slept at their desk,” he said. “And why would I knowingly, if I have the means and opportunity, why do I knowingly subject my baby to the possibility of violence, bullying, hate, anger, not to mention poor education.”

Murrell said forming St. George will allow more tax dollars to stay in the area, and eventually, allow the city to form a school district that he said will be better than East Baton Rouge Parish Schools. He said he knows from his personal experience in a small Texas school system that smaller school systems work better. East Baton Rouge has been failing students for too long, he said.

“Middle class families in this parish shouldn't be forced to fund a private education,” he said.

When it comes to the exclusion of black and latino neighborhoods from St. George, Murrell said it was political strategy, but it wasn’t based on race.

“Demographics are irrelevant to me,” he said. “We wanted the votes, and we went where the support was located,” he explained. He said organizers drew the map to include areas where they had gathered the most signatures for their petition to create the city. Black and latino neighborhoods largely did not support the petition, so organizers left them out. Now, they can’t vote against it, which makes the ballot measure more likely to pass.

Murrell said that later if St. George succeeds and forms a school district, the school system could include neighborhoods left out of the city. School district boundaries don’t have to match city boundaries.

He said residents in the proposed St. George area are underrepresented in the Baton Rouge Metro Council, and that the real reason the rest of Baton Rouge is opposed to St. George is because the area has been “subsidizing” the rest of the parish.

“They don't want us to create the City of St. George. They want us to stay unrepresented in the unincorporated area so things can happen just like they always have been,” he said.

"You have to get back to why this started, and what's the core problem, and why it truly started" - Arthur Pania

“Britain told America the same thing....We got tired of that too. It worked out pretty well for us, America.”

For Murrell and other supporters, St. George is about America -- it’s about independence, freedom and self-governance. But for opponents, like M.E. Cormier, St. George is also about America and its ongoing battle for equality and justice.

“We are better together,” Cormier said. “The community is going to suffer if we can't provide education equally for everyone.”

WWNO’s education reporting is supported by Entergy Corporation.