It’s been 60 years since four New Orleans first-graders walked through the doors of two all-white elementary schools. Ruby Bridges, Leona Tate, Tessie Prevost and Gail Etienne became young Civil Rights leaders in a new push for school integration in the Deep South.

It was not the first time children and their parents led a movement for education access in New Orleans. Almost 100 years prior, a similar campaign led to the integration of the public school system. It was only seven years before segregation again took hold.

Today, while no longer segregated in the traditional sense, inequities persist in many Louisiana schools.

“We have work still left to do,” said Orleans Parish School Board President Ethan Ashley at an event Friday honoring Bridges. “It's unfortunate that I am unable to tell a young group here that we have made it because we haven't.”

A recent report from Measure of America, a nonprofit that maps opportunity and well-being in America, found that while education continues to improve in Louisiana overall, Black residents report worse outcomes than their white peers.

According to the report, New Orleans has one of the highest education scores in the state at 5.79 out of 10, but it’s skewed by the city’s white population. For example, 65 percent of white residents have a bachelor’s degree compared to 18 percent of Black residents.

The gap between Black and white education index scores statewide is 1.34, but in New Orleans, the gap is three times as large.

More than 90 percent of New Orleans public school students identify as people of color and 80 percent identify as Black.

White children account for 20 percent of the city’s population under 18 years of age but less than 9 percent of the public school student body. That’s because white children largely attend private schools.

Divisions like these are common in Louisiana, according to Kristen Lewis, director of Measure of America and author of its new report.

“When educational resources are inequitably distributed as they are in Louisiana today, opportunity gaps widen and inequality can really grow,” Lewis said. “The good news is that just as people and policy can create inequality, they can also dismantle it. Through better choices real progress is possible.”

Lewis said that’s the purpose of the nonprofit’s report: Highlight disparities across the state with the hope that public officials use their research to steer resources toward high-need areas.

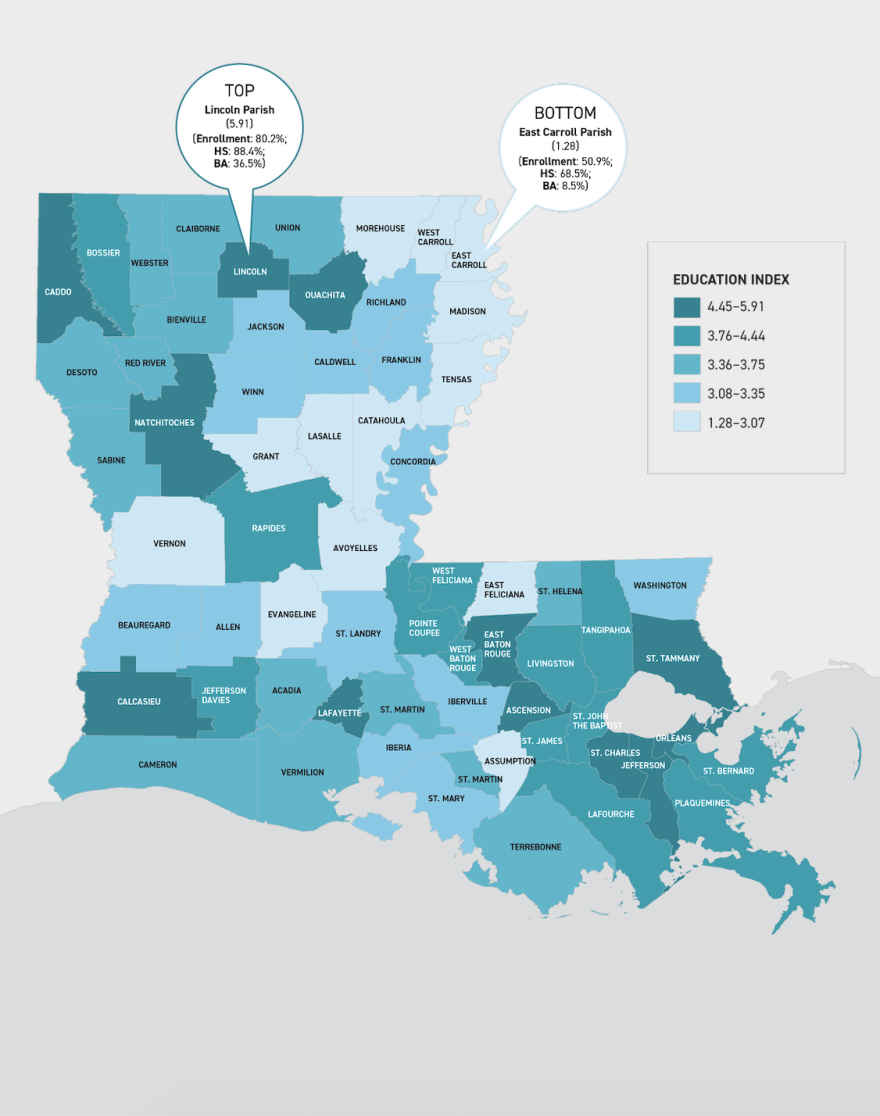

While the state has made progress since its last report in 2009, Lewis said stark inequalities still exist, mainly between Black and white residents, especially when it comes to educational attainment. For education, the report looks at degree attainment as well as school enrollment.

“When you look at the state as a whole, you see huge inequalities if you look by parish,” Lewis said. “But then when you go down even lower and you look at census tracts, you see even wider disparities.”

According to Lewis, one of the strongest indicators of a child’s educational attainment is the educational attainment of their parents. This is where structural racism can have its largest effects.

“From slavery to Jim Crow and the Black Codes and residential segregation, all of these factors really conspired to limit the educational attainment of Black people for a very long time,” Lewis said. “That legacy is still in effect.”

School Segregation In Louisiana’s Capitol

Urban parishes, like Orleans and East Baton Rouge, are more likely to exhibit large disparities due to residential segregation, school choice, and local control, according to the report.

Lewis brings up Louisiana’s capitol as an example. In Baton Rouge, white residents in the suburban neighborhood of Kenilworth max out the education index with a 10. Nearly 7 in 10 residents have bachelor’s degrees and 4 in 10 have graduate degrees.

Compare that to Istrouma and Dixie, majority Black neighborhoods in the city’s urban core. The census tract containing both neighborhoods has an index score of about 1. Three in 10 adults didn’t complete high school and 40 percent of 3- to 24-year-olds aren’t enrolled in school at all.

Like New Orleans, white students in Baton Rouge are more likely to attend private school than their Black peers, according to Lewis. While Baton Rouge has a traditional public school system there’s also a growing number of charter schools.

Lewis said there’s nothing natural or inevitable about inequalities, instead they can be traced back to state and local policies.

“School choice has been a real driver for school resegregation in Louisiana,” Lewis said.

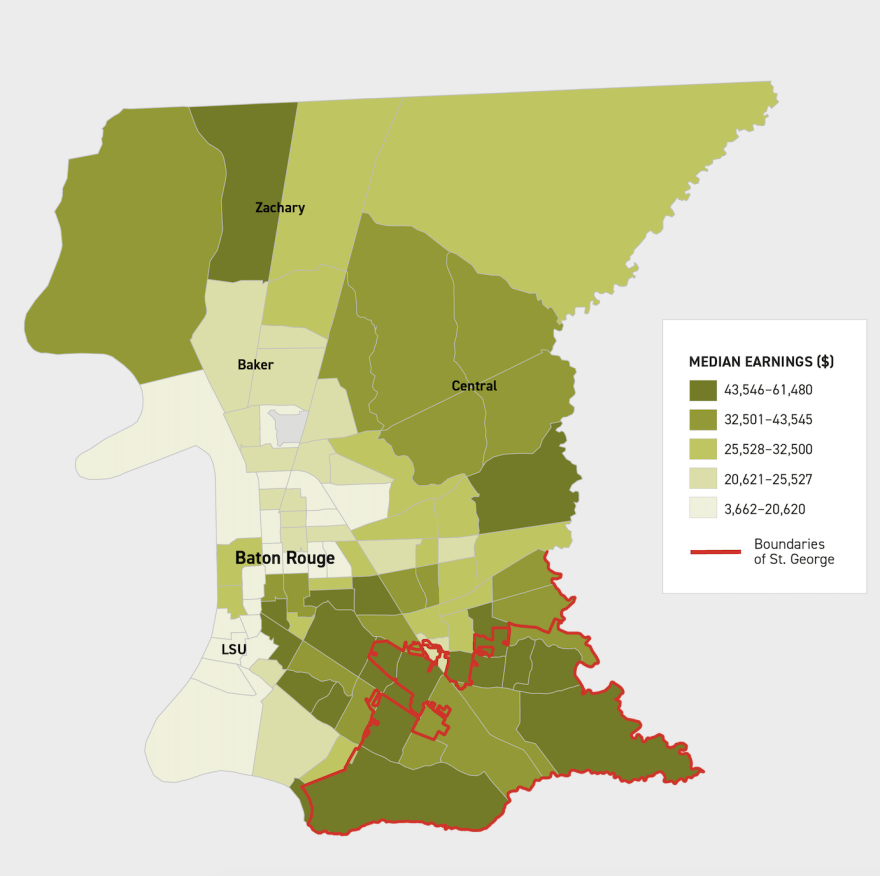

When discussing Baton Rouge disparities, Lewis also brings up the case of St. George.

Last year, residents living in the city’s southeast corner voted to secede in order to create a school district of their own. St. George is whiter and wealthier than Baton Rouge as a whole.

Lewis describes St. George’s retreat as an affront to an egalitarian public school system, one that should be economically integrated and racially diverse.

Because school funding models depend on local property taxes, Lewis said the splits are monetarily motivated.

“Parents cordon off resources to educate their own children rather than all children,” Lewis said.

Across the country at least 128 communities have attempted to form their own school districts since 2000, according to EdBuild, a site that details school funding. At time of EdBuild's last report, seventy-three splits were successful.

Closing The Gaps Means Investment At All Levels

One of Louisiana’s biggest areas for improvement is college completion. According to the report, less than a quarter of Louisiana adults 25 years and older have a bachelor’s degree, compared to about 33 percent nationwide.

There are many reasons why someone may choose not to attend college, but a common one is cost. In recent years tuition has climbed and per-pupil college spending has dropped.

Lewis said these trends must reverse if Louisiana wants to close racial gaps and catch up to the rest of the country.

Many Louisianians spend their entire lives in-state. In New Orleans, teenagers often set their sites on the city’s HBCUs or enroll at a public college or university. Very few attend Tulane University, the city’s most well-financed institution.

About 90 percent of Tulane’s student body is from out of state. Recognizing this, Tulane announced last week it’s looking to change.

The university will provide debt-free financial aid for Louisiana high school students admitted as full-time students next fall.

Lewis said another way to improve educational outcomes is to invest early.

“Preschool is one of the best investments society can make,” Lewis said. “It has huge impacts not just on school readiness, but also on high school completion, and on all kinds of long term outcomes.”

Louisiana has already displayed a commitment to early education and enrolls more students in preschool than the national average. About 51 percent of 3- and 4-year-olds are in school compared to 48 percent nationwide.

Black children in Louisiana are more likely to attend preschool than white children, according to the report. More than 60 percent of Black children are enrolled compared to 47 percent of white children.

Lewis said this is likely due to the success of Head Start programs and other publicly funded preschool programs that operate in low-income Black communities.

Between 2014 and 2020, Louisiana secured three federal early childhood grants totaling more than $72.1 million. Much of the money was used to serve high-need communities.

Lewis said the next step would be for the state to provide free PreK for all 4-year-olds and further expand programming for 3-year-olds.

Nearby states like Florida, Georgia, and Oklahoma already offer universal PreK, which Lewis said can also help address the childcare crisis created by the coronavirus pandemic.