Early in the evening of Friday, August 27th, 2021, New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell stood at a City Hall lectern and delivered an update on the approach of Hurricane Ida.

The situation had grown more serious since Cantrell last addressed the public, six hours before. Then, Ida had been a tropical storm. But it picked up speed over the course of the day, and by 4 p.m., the National Hurricane Center predicted Ida would become an “extremely dangerous major hurricane” by the time it approached the northern Gulf Coast on Sunday.

“Hurricane Ida developed and has been developing more rapidly than anyone was prepared for,” Cantrell said. There would not be enough time to issue a citywide mandatory evacuation — only one for the areas outside the levees in Orleans Parish.

“Time is not on our side,” she said.

When a storm as strong as Ida sets its course toward southeast Louisiana, officials in New Orleans typically consider issuing a citywide mandatory evacuation order. That means all residents and visitors must leave, either by their own means or with help from the city.

To make that happen, officials maintain the City Assisted Evacuation plan, designed to evacuate people who don’t have a way to leave themselves: it outlines the coordination of a central evacuation hub at the Smoothie King Center, trains with Amtrak, planes with the airport, buses with the New Orleans Regional Transit Authority, and more.

The CAE plan was developed in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, and has only been implemented once ahead of a storm, for Hurricane Gustav in 2008.

But it revolves around having at least 72 hours of lead time before the winds of a major hurricane hit the coast.

Rapidly intensifying hurricanes like Ida, which are becoming more common, do not afford that much time.

At a press conference kicking off the 2022 hurricane season on June 1, Cantrell said emergency officials are shifting plans to tackle fast-forming storms that don’t allow enough time for a citywide mandatory evacuation.

“It’s, I know, at the top of my mind,” Cantrell said. “And keeps me up, quite frankly, in the middle of hurricane season.”

A break from the past

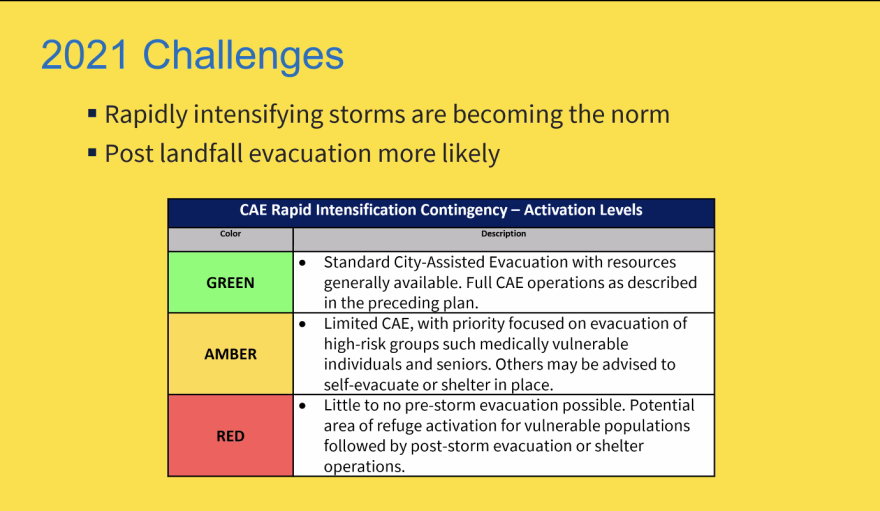

This year, emergency officials have amended the CAE plan to include a Rapid Intensification Contingency section for the first time. It lays out three potential color-coded “activation levels” that depend on how much time the city has before a hurricane hits, and what resources are available.

View a copy of the CAE, obtained by WWNO, here.

In the Green scenario, which is essentially the city enacting the original CAE plan in full, the city has 72 hours or more to anticipate a major hurricane.

Under this plan, all evacuees are supposed to be out of town 30 hours before tropical storm force winds hit the coast. It’s designed to move about 10% of the city’s residents, or 35,000 to 40,000 people – particularly those without cars or with medical needs. The city counts on the rest to evacuate on their own.

That timeline fits within a larger evacuation plan maintained by the state, designed to evacuate southeast Louisiana in phases, from the coast up through metro New Orleans. In an ideal scenario, the City Assisted Evacuation portion would be finished before the state implements contraflow, allowing traffic to run one way on interstates heading inland, said Collin Arnold, director of the New Orleans Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness.

Pulling off a full-scale, pre-storm evacuation – which Arnold described as the “safest option” ahead of a major storm – is near impossible with less time.

“At that point, it’s very difficult to get all of those pieces together,” he said. “You can still offer, or order, a mandatory evacuation, but then you have to realize: what are you going to do with the folks that can’t get out? What opportunity do they have? That’s kind of where we’re at right now, and why we’ve made some changes that we think can address this.”

The new additions to the plan fall under the “Amber” and “Red” scenarios, which take into account the challenges planning around a faster-growing storm.

For a hurricane that undergoes a period of rapid intensification, its peak wind speed must increase by 35 mph within one day. Last year, Ida met that threshold in six hours.

Atmospheric scientist Allison Wing said it’s only the latest in a string of storms that have strengthened faster than anticipated. In southwest Louisiana, Hurricane Laura was one of 10 storms that rapidly intensified within the 2020 hurricane season.

She said it’s happening more often, nearly doubling in frequency in the past five years.

“Those are typically the most dangerous storms,” Wing said, noting that the majority of Category 4 or 5 storms rapidly intensify at least once before landfall.

Scientists and forecasters are still figuring out what’s driving the change, but hotter ocean temperatures driven by climate change aren’t helping. Studies have shown warmer waters have led to stronger storms, but how they have affected the rate of intensification has yet to be proven — though Wing wouldn’t be surprised if it was related to global warming as well.

The trend isn’t expected to reverse, and as rapid intensification remains challenging to predict, early preparation remains key, she said.

In the city’s new Amber scenario, New Orleans would have closer to 48 hours before the arrival of tropical storm force winds to work with, which could mean there are not enough buses or shelter space available “to accommodate all who might wish to evacuate,” according to the plan.

The city would then use available resources to evacuate its “highest-risk populations first” ahead of a hurricane. Those groups are defined as “medically vulnerable” people, including those who need dialysis or who rely on equipment that requires electricity to run, as well as elderly people, like those living in the senior apartments where post-Ida deaths were concentrated.

Arnold said they would move more people outside of that priority population after the storm hits.

The Red scenario would apply to situations like Ida, Arnold said, when there is little time and few resources available, meaning “you’re not going to be able to move people.”

In this scenario, residents who are able to leave on their own would be encouraged to voluntarily evacuate if road conditions are safe and there is enough time before severe weather hits. Others would be advised to shelter at home, or go to a “city-designated, last-resort ‘refuge’ location” for protection during the storm itself.

After the storm passes, the city would assess the impacts and either focus on a post-storm evacuation or may transition its areas of refuge into longer-term shelters.

If damage is widespread and basic services are shut down — particularly “if we’re flooded out,” Arnold said — then moving people out on a large scale would be necessary, he said.

It took the city nearly a week to offer shelter and post-storm evacuation options after Ida. When asked if he felt confident that the city could start the post-storm evacuation process sooner, Arnold said, “without question.”

“I think now, based off the lessons learned from Ida, that we plan for a seven- to 10-day power outage no matter what,” Arnold said. “If that’s the case, then we move people when it’s safe. Can it be immediate? Probably not. Twelve to 24 hours? Yes, I think so.”

If the hurricane’s impacts are less severe, then the city may pivot to opening local shelters, focusing on “particularly vulnerable populations” and individuals who lost their homes, Arnold said. His office is now working closely with New Orleans Recreation Development Commission (NORD-C) employees to help expand post-storm shelter capacity within the city, he said.

This year, “our goal is more. Go bigger,” Arnold said, of local shelter capacity. “Instead of a hundred [people], let’s do a thousand.”

Experts express concern over gaps in contingency plan

Emergency planning experts who reviewed the city’s plans at WWNO’s request raised concerns about the lack of detail in them, as well as the lack of public messaging around them.

Alessandra Jerolleman, a senior fellow in the Disaster Resilience Leadership Academy at Tulane University, said she was disappointed by the plan’s brevity, and the lack of certainty around options for a worst-case scenario.

“It’s absolutely not a promise, not enforceable. It’s just an idea,” she said.

Jerolleman pointed to the Amber scenario, in which the city would evacuate a limited number of residents pre-storm.

“If you have people showing up at a site that can’t evacuate — the vast majority of them — how do you then get them home? How do you turn them away?”

Miriam Belblidia, director of programs for Imagine Water Works and a former hazard mitigation specialist for the city, noted the lack of clarity around who can and cannot evacuate under this scenario.

“If there’s a grandmother who’s the primary caregiver for a younger child, I have questions about what would happen, and how that would be handled, and how people might be separated,” she said.

In response, Arnold said that people at high risk of heat-related illness and those with pre-existing medical conditions will be prioritized, working closely with the New Orleans Health Department. He emphasized that households will not be separated, and said that if more people come to the evacuation hub than there is capacity to move ahead of the storm, they will be directed to a refuge.

When it comes to the Red scenario — in which the city would not evacuate anyone pre-storm — the plan itself notes that NORD-C facilities or the Convention Center “may” be used as refuges, “depending on the size of the population in need.” They would be intended only to provide “short-duration protection from the elements.”

That lack of certainty worries Jerolleman, noting the city’s “cavalier attitude” toward establishing a shelter of last resort before Hurricane Katrina, when residents came to the Convention Center to find few essential supplies available.

“We're back to having a ‘maybe,’ and I find that really, really concerning and frightening,” Jerolleman said.

Arnold said he understands these concerns, but “it really does depend on what the situation is on the ground.” The city maintains a list of possible sites for refuges and post-storm shelters — all city or state owned buildings — and sites are determined based on their availability in real time, factoring in backup power sources and storm damage. He also said the city maintains a supply of water and MREs, and typically expects the Federal Emergency Management Agency to bring in more.

Details on the contingency plans have not been widely publicized beyond a few public meetings this spring, and several neighborhood training sessions so far in June.

But the Green, Amber and Red scenarios are mostly intended as internal guidelines, Arnold said. Public messaging has focused on explaining that there may not be time to fully implement the CAE plan, he said, and that the best things to do are stay connected to updates from NOLAReady, as well as register for Smart911, a new program the city is using this year to identify people with medical and mobility issues in place of the former special needs registry.

John Renne is a professor of urban planning at Florida Atlantic University and previously worked at the University of New Orleans for a decade, where he studied the city’s evacuation plans extensively. He said historically, many aspects of the CAE have been kept somewhat hidden from public view.

“It kind of puts people into a point where they can’t really plan for themselves and their family members,” he said.

Jerolleman echoed that point. She would have liked to see a more public process around developing these contingency plans, as well as more concerted outreach at the start of hurricane season.

“Any of these plans are really only as good as people’s awareness of what to do and where to go,” she said.