Editor's Note: This story is part of a reporting fellowship sponsored by the Association of Health Care Journalists and supported by The Commonwealth Fund.

The three-part series examines the opioid crisis in the United States and the Gulf South and compares it to successful drug use harm reduction efforts in the Netherlands. You can read other entries in the series here:

- Part 1: Going Dutch: Harm reduction is embraced in the Netherlands but struggles in the US

- Part 2: Netherlands police embrace a public health approach to drugs. Will it work in the South?

- Part 3: Drug checking services save lives in the Netherlands. The Gulf South doesn’t have any

On Saturday, July 12, Dani Sims got a call with some bad news. Two men she knew from Birmingham’s homeless community had died after using a batch of toxic drugs circulating in the city.

Sims works at Recovery Resource Center, helping people navigate Alabama’s fractured drug treatment system. With lived experience in recovery, she’s deeply connected to the people most at risk. She started calling around.

What she learned: the drug was a dark-colored methamphetamine. One man told Sims the “brown meth” caused pain so excruciating it felt like “fire going through his veins.” Another said he begged his partner to call an ambulance — a significant act for Sims.

“That’s a really big deal for someone who's experiencing homelessness, faced with all that stigma, to rely on the health care system — to go to the emergency room,” she said.

Sims wanted to warn others. But in the U.S., there is no official system to test suspicious drug samples or alert the public about them. So, she had to do it on her own.

The following Monday, Sims’ organization reshared a social media post about the brown meth. She contacted Jefferson County’s coroner and health department. She also went searching for people she worried might be at risk.

One was Michelle, a woman in a wheelchair Sims first met during a freezing winter night at a warming station. Michelle had a leg amputated, suffered a stroke that left her with one working arm and had recently been hit by a car when Sims met her.

She needed long-term care, but nursing homes turned her away because she couldn’t manage her daily needs and she used drugs.

That left her sleeping in a Birmingham park, waiting for a facility that would take her. Sims went to the park to look for her. But she wasn’t there. Then, she got another call. On Tuesday, July 15, Michelle had been found dead in her wheelchair in the parking lot of an abandoned business downtown.

The brown meth reached her first.

“And that’s just devastating because where are the resources for people like that?” Sims said. “She was actively seeking treatment. Why was there not a resource to provide for her?”

The ‘red alert’ that never came

According to the Jefferson County Coroner’s Office, Michelle and at least four others in Birmingham died from an accidental overdose caused by a toxic mixture of fentanyl, fluoro-fentanyl and methamphetamine between June and July. Cutting agents like lidocaine or quinine were also found in their system, which may have worsened their condition.

No official warning about the brown meth ever went out in Birmingham.

Had the same drug appeared in the Netherlands, however, it would have triggered a nationwide “red alert” within 24 hours — pushed out on TV, radio, newspapers and social media.

That system is possible because of the Drugs Information and Monitoring System (DIMS), a Dutch national drug checking program where people can anonymously submit samples to labs. DIMS, run by the Trimbos Institute and funded by the government, analyzes those samples and tracks dangerous drugs as they spread. If a toxic batch is found, the public is warned immediately.

“If we would find, for instance, fentanyl or nitazines in MDMA powder, we would probably immediately warn either tonight or otherwise tomorrow,” said Daan van der Gouwe, a drug researcher at Trimbos.

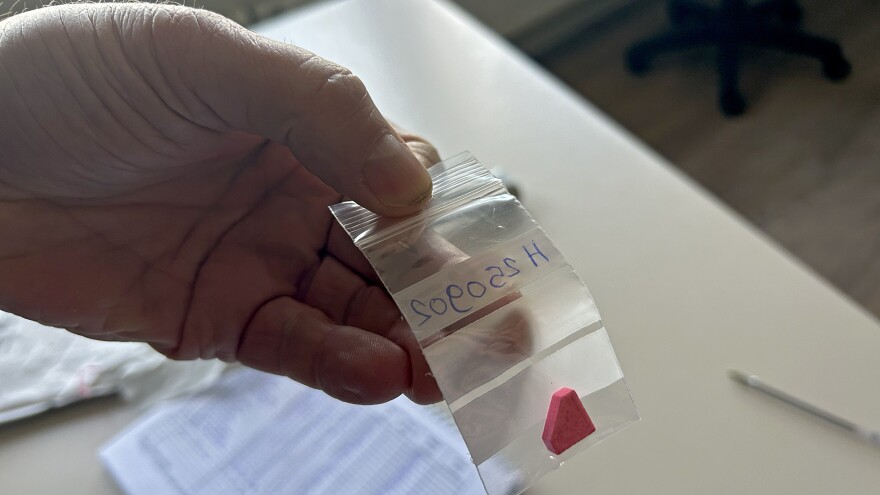

Van der Gouwe also appears in radio and television interviews during a red alert — as he did in 2015, when pink, Superman-logo pills of toxic MDMA were detected. Because of the warning, nobody in the Netherlands died from them.

But in the U.K., where no such system existed, the same pills killed at least four people.

“Preventable death, I’d say,” van der Gouwe said. “But in a lack of a good system there, this happened.”

A ‘third way’

Both the U.S. and the Netherlands wrestle with the politics of drug use, but their approaches diverge in key ways that reflect deeper ideological divides.

In the Netherlands, drug use is largely seen as a public health issue. Harm reduction strategies like drug checking and red alerts are integrated into national policy.

But drug checking wasn’t always accepted in the Netherlands. In the late 1980s, as ecstasy and other club drugs spread, activists like August de Loor pioneered a different approach.

“The first way was police — criminalize the user. The second was clinics — isolate them from society,” de Loor said. “The third way was to accept the use of drugs in a social environment and setting, and accept the risks. Don’t turn away from it, but minimize the risk.”

De Loor launched the Safe House Campaign in 1989, providing harm reduction at parties — from first aid to on-site drug testing. By 1992, the government had formalized the effort into DIMS, creating a national database to track drugs and coordinate warnings.

“It was amazing,” de Loor recalled. “The Dutch government gave us room that we could do that.”

It wasn’t without pushback.

In 2002, Dutch lawmakers banned on-site festival testing, fearing it legitimized drug use. Drug checking became office-based, where samples are dropped off for lab analysis. Still, the infrastructure remains: a network of local sites connected to a centralized monitoring system — something the U.S. has never had.

Politics and punishment

As much as the Netherlands has progressed when it comes to drug policies, the consensus of the public health approach is currently under strain.

“Traditionally we’ve had a history of harm reduction-focused policy, but in the last couple of years a focus on repression has been getting the [upper hand],” said Joost Sneller, a Dutch parliamentarian with the liberal D66 party.

The shift coincided with the rise of far-right leader Geert Wilders, often called the “Dutch Donald Trump.”

Wilders has pushed nationalist, anti-immigration policies and deep cuts to social services. Under his leadership, funding for drug checking services like Trimbos has been slashed, with a 20% budget cut looming by 2026.

Still, even with backlash, the Dutch maintain a robust harm reduction infrastructure. The U.S. does not.

In July — the same month Michelle died in Birmingham — President Trump signed an executive order to cut funding for “so-called harm reduction” and “housing first” programs. It also encouraged states and cities to criminalize homelessness, enforce bans on public drug use and prioritize policing over services.

In Alabama, the closest analog to drug checking services is fentanyl test strips, which only became legal in 2022. Other harm reduction practices, such as syringe exchange and safe consumption rooms, remain prohibited.

Sims said she’s seen progress in some harm reduction services, but basic practices remain underground.

They may never “fully be in the light,” she said.

Had she been in the Netherlands, Sims said, Michelle would have had access to long-term housing, despite her chronic drug use. She would have had access to harm reduction resources, like drug checking services and safe consumption rooms, where she could have used drugs she knew weren’t toxic under medical supervision.

Instead, the drug treatment system in Alabama failed her, Sims said, and Michelle died an agonizing death alone in a wheelchair in a downtown Birmingham parking lot.

For her, that’s what’s most difficult.

“What happens next time?” Sims said. “What happens for the next Michelle?”

This story was produced by the Gulf States Newsroom, a collaboration between Mississippi Public Broadcasting, WBHM in Alabama, WWNO and WRKF in Louisiana and NPR. Support for public health coverage comes from The Commonwealth Fund.